Haruhiko Shono

A Prophet of the Digital Age

Profile/Interview

- 01 / 10 / 09

In February of 1995, Newskeek magazine published an article entitled "50 For the Future"

, introducing a selected group of visionaries from different fields of computer technology. Among a predominant majority of North-American names, composed of businessmen, journalists, physics, engineers, computer systems and software developers, the inclusion of Haruhiko Shono, representing the digital games domain, was by no means startling.

Shortly before the turn to the 1990's decade, the Personal Computer industry was embarking on a decisive process of unification with emerging and alternative forms of art. Consequentially, the use of CD-ROM as the standard media for software publication would cause dramatic changes to the digital games industry, namely with the inclusion of video and pre-recorded high quality audio. This unprecedented cutting-edge resource conveyed new possibilities that succeeded in fascinating movie makers, musicians, and painters among many other accomplished artists.

It was in this precise context that Haruhiko Shono was drawn into the trade of videogame design, after refining his techniques in the world of digital video production and computer graphics. Teaming up with fellow artists, he signed a contract with videogame publisher Synergy and Toshiba EMI for the conception of a hybrid PC and Macintosh game: ALICE - AN INTERACTIVE MUSEUM, released in 1991, was one of the earliest subjective point-and-click adventures using pre-rendered images.

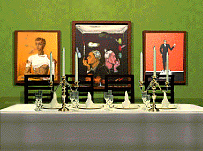

Inside the unique space of a virtual museum, the player is able to discover the surrealist paintings of Kuniyoshi Kaneko, inspired by theme of Lewis Carrol's literary masterpiece Alice in Wonderland. Scattered throughout the different rooms of the gallery is a deck of playing cards which the player must retrieve, while interacting with the tantalizing puzzles in the form of pictures. On account of its effective tridimensional promenade and highly artistic values, ALICE won the AVA Multimedia Grand Prix MITI 's Minister's Prize in 1991.

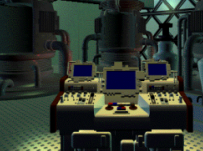

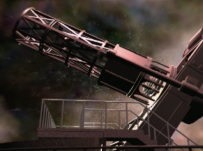

Continuing his work with Synergy, Shono unveiled a similar adventure scheme in yet another PC/Mac title under the name L-ZONE, published in 1992. Experimental and mysterious, its cybernetic environment was unlike any other in its day: amidst the large industrial venues and silos overflowing with mainframes and other electronic paraphernalia, the feeling of solitude and lack of concise objectives helped to build up an outlandish form of tension: paradoxically, Shono and his team generate this scenery of technological asphyxia using the computer as medium. Its audiovisual excellence, namely the vanguardist techno sound clips and loops, appealed to different players on an international scale, making L-ZONE one of the best sold products of its time and the winner of the '92 Multimedia Association Chairman's Award.

The year of 1993 was of particular importance to the pursuit of Haruhiko Shono. Taking exceptional advantage of the maturation of the game design techniques employed in his debuting titles, he generated an original project which would later become the indisputable reference of his professional career: GADGET: INVENTION, TRAVEL AND ADVENTURE, distributed that year in markets around the world, would soon convert itself into one of the most influential digital works ever made. Combining 256-color images with black and white Quicktime video technology, Shono molded a virtual sphere interweaving art deco with industrial design as background for the depiction of an obscure future where reality and induced illusion are indistinct.

In GADGET, Shono expressed his exceptional taste for machinery, not only with recurrent use of trains, the suggestive one-track means of transportation recurrently used during the game, but also with the introduction of a vital element to the brilliant narrative named the Sensorama - a menacing device capable of altering the perception of reality. While the narrative was intricate and exceedingly ambiguous, unlike any other in its day, the sheer visual spectacle and intriguing ambience caused quite a shock among the unwary community of players, generating enough sales to have GADGET rank as one of the best-selling multimedia CD-ROMs of all time - and, once more, winner of the famed Multimedia Grand Prix.

From 1993 to 1997, Shono sought to explore the potential of this dark futuristic setting further. Not long after the release of the game, a book under the name Inside Out With Gadget was published, comprising an impressive number superior computer generated images together with a series of written texts in the form of memos, reports and diary entries scientists, politicians and other characters portrayed in the game. Soon thereafter, the Gadget Mindscapes film followed, using video rendering quality that was impossible to include in the game, accompanied by an extended version the ethereal soundtrack composed by Koji Ueno.

The final installment of this universe was perhaps the most significant of all: recreating the original game, Cryo published GADGET - PAST AS FUTURE, a remake of the 1993 game using new and improved full-color video sequences, as well as extended features that were not available before. This release reignited the interest for the game, in an impressive 4 CD release that was translated and dubbed into several languages. In spite of the awards and recognition from a die-hard CD-ROM public, the last half of the decade was invariably defined by the growth in real time 3D technology. The technologies in which Haruhiko Shono specialized throughout his career, based mostly on CGI and Director-based programs, were demoted from dominant to auxiliary. Because of such radical changes in the industry, GADGET: PAST AS FUTURE became his last project as a game designer.

With the increasing demand for pre-rendered computer graphics technology in the fields of film and television, Haruhiko Shono opted to face new challenges. The most notable of which was the 2004 motion picture Casshern, a Japanese science fiction and fantasy motion picture that thrilled audiences from all over the world. Based on an early TV Anime series, this film was often described by critics as Japan's answer to Hollywood's special effect blockbusters, since Casshern presented special digital treatment for almost every shot. Shono participated actively in the production of the film merging live action footage with digital backgrounds and additional special effects.

In spite of pursuing different objectives, he kept close contact to the videogame industry in some occasions: after directing CGI in KAMAITACHI NO YORU 2, a PS2 release exclusive to Japan, he felt fascinated by the potential of new generation console technology when joining the Chunsoft staff for the creation of the PS3/Wii horror title IMABIKISOU. Nevertheless, the exceptional reputation he earned during the golden years of the compact disk era lost strength, progressively, to the point where his name slowly ceased to appear in magazines, newspapers or award ceremonies; unforgiving, the march of videogame progress led to the neglection of an artist who had once prophesized it.

The title screen for GADGET (1993).

More than a decade after the release of the definitive edition of GADGET, I looked for ways to establish contact with this author whom I regard to be a reference in the chapter of videogame creation. His games, often accused of being linear, bear witness of a different conception of what this medium could have been had all designers and creative minds shown such appreciation for quality and maturity.

In return for all my efforts I was granted an exclusive interview with more substantial and descriptive answers than what I could ever ask for. I would like to acknowledge the translator, Sorrel Tilley, for having performed an exceptional work in keeping the original integrity of the text; furthermore, I will forever beindebted to Haruhiko Shono: not only for his decision to participate in this interview, but most of all for having created some of the most important videogame experiences of my life.

-------------------------------------------------------------

COREGAMERS : Even before completing your studies, you started to develop several works that were closely related to high definition video, computer graphics and new media in general. What has captivated you in these new forms of expression?

Haruhiko SHONO : Although I studied Graphic Design at university, I was more interested in images and music than in paper-based design, so, taking influence from video artists like Bill Viola and Nam June Paik, I began work on video projects. Original music was necessary too, so I also began composing using a PC at this time. From then on I made use of various technologies and came to create Ďnew mediaí video works, so to speak. In 1985 I formed a performance group called ĎRadical TVí, and at concerts we would set the stage with a giant screen and tens of other monitors and create a video in real time, similar to current VJ video performances, as they are called, although, because they were improvised in a short time, the style was radically different from modern creations.

CG : I assume there must have been some serious limitations imposed by the technology available at the time: what sort of techniques and software did you use back then?

SHONO : At that time, the main piece of equipment we used was a Fairlight CVI (Computer Video Instrument) for real time image processing, and even now, it is very impressive. After that, with the introduction of Commodore’s Amiga, the popular process of video production at that time began to move away from video photography and in-studio editing, toward personal desktop works. It was also around this time that I began making full-blown CG-based animation in both 2D and 3D. However, because at that time I was using media recorded to floppy disks, I had to come up with ways to work within the restrictions of a limited data capacity and colour palette.

For example, the data for a TV programme’s title sequence would take up 5 whole floppy disks. Before CD-ROM technology came about, high storage capacity media, like we have today, was inconceivable. I was only able to make low resolution videos, but I came to have confidence in the potential of desktop video creations. I think the appeal of the expressive power of this medium is being able to witness the unfolding potential of expressiveness, thanks to technological innovation.

It’s very stimulating to see expressive power advancing, regardless of personal skill level. However, because the expression itself is also swift to grow stale, it’s often the case that hard work made during that time span amounts to nothing. Nevertheless, the moment you touch on a new expressive possibility, it’s always stimulating and deeply interesting.

CG : It was only sometime after that you decided to explore the potential of CD-ROM, having created a group of videogames or interactive experiences that received some of the most important Multimedia awards of their day. By then, what was your opinion of the video game medium - were you a video game player?

SHONO : Around 1989, I was doing work in TV and video which took very little time to complete, so I desired a project that would require more time and careful deliberation. This was the period when the creative environment, based on Mac technology, also allowed for high resolution video works, and the likes of Photoshop and MacroMind Director (now Adobe Director) had come out, so I wanted to produce a work that, even with a single picture, could have persuasive power. Also, I was busy with several CD-ROM works, so it was very confusing. Actually, I wasnít so interested in video games originally and had only played a handful of Amiga games.

Nevertheless, I felt that video games had a certain allure, and many possibilities that were lacking in other types of video media. The allure was the interactivity of games, and they were a digital media that allowed video works in full CG. Movies and videos in linear media are limited to the axis of time, and production cannot escape those limitations. Furthermore, this was the period that movies and video began their process of digitization but, fundamentally, they were an analogue medium. Perfect videos in full CG were impossible. At that point in time, CD-ROM was the only medium that made full CG videos possible.

CG : ALICE INTERACTIVE MUSEUM is by far one of your most recognized works, bringing the exquisite art of Kuniyoshi Kaneko into the realm of digital products. Tell me how this joint project started and what did you try to achieve with this surrealist game design?

SHONO : In 1990, I started a project after discussing the transfer of images to CD-ROM with Kuniyoshi Kaneko, who was introduced to me by Masanori Awata, president of the publisher Synergy (who I got to know through magazine research). As originally suggested by the musician Kazuhiko Kato, I was already producing video works using a PC. After that, continuous meetings with Kuniyoshi Kaneko in his home studio resulted in not only his own work, but the transformation of that work into a game. In his studio there was a fascinating collection of work and countless strange items. I considered that compiling them into a simple book of paintings would not reveal their potential; but that as a video game, they could become something else entirely.

His studio was a bewitching place and I went around touching and investigating everything. Seeing the other side of his work, I felt that its contents held a great necessity. At this point we established the game concept of the Interactive Museum, which included Kuniyoshi Kanekoís work. We then photographed an enormous amount of items as raw material, digitized all of them, but I remember what a great trouble it was, because at that time there were no digital cameras. In order to reproduce his room, we used Fractal Designís Mac-based CG creation software - Ray Dream Designer.

Although there was no way we could make lifelike videos, the characteristic quirkiness we achieved is a very impressive addition to Kuniyoshi Kanekoís style. Because ALICE was one of the earliest CD-ROM works, in the initial stages there were a great many challenges relating to the image compression and data transfer rate. A large amount of time was spend on data optimization, and it became necessary to compromise heavily on the part of artistic expression. While the expressive potential was greatly increased compared to analogue media of the time, at the same time we had to confront the many challenges presented by digital media.

CG : L-ZONE and GADGET , on the other hand, are much more linear titles; the first is essentially an audiovisual experience, a demonstration of high-resolution technological landscapes, while GADGET is a story-driven game with characters and dialogue. Was there a particular reason for this change in your design philosophy?

SHONO : ALICE had many small contrivances, but this was because the concept of the Interactive Museum required as much interactivity as possible, and inevitably this resulted in a high degree of freedom. However, it didnít have a strong story, so the flow of the game was too free, and consequently there is a feeling of ambiguity to it. Personally, I think this is due to the fact that I was fussing over the details of interactivity, because it was my first video game.

L-ZONE was published the next year. As a science fiction fan, I had long held the modest desire to infiltrate a forbidden research facility and freely use the experimental technology found there, and we used this as a concept for this small scale project. When compared to my other two works, the preparation phase was short, and I really made it according to my own feelings. Because interactivity was a phenomenon that was narrowed down to the operation of equipment and its effects, when you compare L-ZONE to ALICE, the level of freedom is quite low. Since my aim with this work was to illustrate the dangerous allure that technology holds, it can also be seen as a rehearsal for GADGET.

It can even be seen as proof of my love for different types of machine switches and levers. 1993ís GADGET was originally planned to be a mixture of ALICE and L-ZONE, yet during the development process, we introduced full CG characters for the first time: situations involving conversations with those characters also evolved and it became necessary to attribute meaning and motives to their behaviour. To that end, we clarified the story and the importance attached to freely interactive events was reduced and the structure became more linear. I also think that this linear structure was necessary to maintain tension and to increase the persuasive power of the fictional world.

CG : I recently read an interview in which the Hollywood movie director Guillermo del Toro mentions GADGET as one of the most influential video games ever designed, adding that movies like The Matrix and Dark City were highly inspired by the game. GADGET is an uncommon game even by today's standards. What inspired you to create this unique experience?

SHONO : In 1992 I started to work on GADGET and, as the title suggests, I quickly decided to give it a science fiction setting, expanding on the world I attempted in L-ZONE which was filled with strange devices. However, because I also had many ideas which, as with ALICE, were not science fiction related, I wanted to make a world which also reflected such things. I had long since held an interest in exterior and interior architectural designs which existed in the past but are now lost, as well as industrial goods and designs which were planned but never implemented - I had many ideas of this sort that I wanted to include.

Eventually I wanted reconstruct all of these things in my own way, designing an entire world in which they could exist. Although the genre of the game is science fiction, I was aiming to make a world with a serious, static impression, refraining as much as possible from adding convenient and high powered technology. I had a firm belief that we could manage the creation of such a world using full CG, but I felt that its realisation would also require full CG characters. In practice, the technology we had at that time could not have been used to create realistic characters like those which are possible nowadays. But I remember how hard it was in that atmosphere to produce something, having to make choices of hardware and software, establish a creative technique. The characters that appear in Gadget are like lifeless dolls. This is because in the game world, characters that ask too much and donít fit in are judged.

Although they have the appearance of humans, realistic humans werenít necessary, because what I needed were characters that added tension and persuasive power to this static world. The exposure time for the earliest portrait photos was very long, so the subjectsí poses and facial expressions seem stiff and unmoving: I think the persuasive power of those images is very strong. For example, the portraits of photographer August Sander have a powerful influence on me. One of the things that differentiate GADGET from other games is perhaps that while it used the latest technology of the time, the imagery is strongly reminiscent of the fascinating expressions of the past. Incidentally, I now base my concept designs for movies and games on what I experienced during this creative process.

CG : Shortly after the release of the game, you embarked on the project of creating Inside Out With Gadget, a book that included dozens of high quality renders as well as information that was vital in understanding the full width of the game's narrative. What were your influences for the creation of this colossal project and what software did you use to create it?

SHONO : Although there are many wonderful possibilities for expression in video games, there are also many things which are impossible to express. In the visual book Inside Out With Gadget I wanted to implement the parts which I couldnít express in the game.

Once GADGET was completed, I immediately began expanding it into several different mediums, with the three types being books, video, and live concerts. First, I determined the differing units of time required for development in each of these mediums; games took days, books took years, videos took hours, and concerts were real time personal experiences. Thus, I wanted to bring the world of GADGET into several different time axes. Inside out with Gadget takes advantage of the superior quality of the printed word and the story is made gripping by the fact that it flows randomly through time and space; the text abandons the form of conversation and explanatory notes, and instead takes the form of correspondance between all the characters. I made it this way because I thought it would make best use of the strengths the book format allows.

I was also aiming for the feel of a photo album, documenting the world of GADGET in images, bearing in mind the indirect and ambiguous expressionism of the game, while steering clear of a direct and explanatory vision. In the game world there are only simple backgrounds, so to enable an increase in the graphical settings, I rebuilt and made additions to the models. After that, when I was working on the scenes in the second half, where civilisation is gradually crumbling, I became extremely fixated on the forest scenes, as a counterpoint to the fact that up until then it had been full of man-made things.

The software I used for models was Macís Electric Image and formēZ, and SGIís Softimage. Image processing was done in Photoshop. Of all these, the only software I continue to use even now is Photoshop.

CG : In L-ZONE, technology is presented in the form of danger and mystery, much like in GADGET. Why did you choose to portray technology as an element that inspires fear and oppression and at the same time wonder and awe?

SHONO : As a child, I loved science fiction films and books, and Iíve maintained a keen interest in technology since then. However, technology has both a positive side of imagination, possibilities and a negative side of danger, which is also very captivating. I think dealing with the balance between the positive and negative aspects of technology as a theme is very thrilling. Because of that, my works are rarely optimistic entertainment pieces. I also often deliberately use sound oppressively to create a high tension environment, and because of the presence of danger, it tends to amplify the gloomy atmosphere.

CG : During your career in Synergy you had the chance to work with top quality artists such as Koji Ueno and Kazuhiko Kato. How did these artists react to your invitation to work on a CD-Rom product? (Most artists don't recognize the potential of video games, so I've often wondered how distinct composers such as these faced the task of creating music for a video game.)

SHONO : Koji Ueno and Kazuhiko Kato have a strong interest in video as a medium, and also research the relationship between music and video. Video games also peake their interest and I think they took pleasure in participating: I received much encouragement from them both when they had a look at videos I was working on.

My own personal preference in music was not for so-called stereotypical game music and so for ALICE and GADGET, I requested a type of music not ordinarily used in games. Even for them, there were parts that became musical challenges, but it wasnít anything that negated the possibility of doing a game. However, they let me know in advance that they understood that compromises would be necessary, given how music is used in terms of the nature of video games. Consequently, their collaboration was not problematic in the least, in fact it was very constructive.

CG : Though information is scarce, I find there is a long period of absence in your life from the video game medium. In spite of that, you were given the chance to work for a motion picture, Casshern, a film best known for its rare aesthetic and impressive visual effects - what was the nature of your work on the project?

SHONO : Iím not fixated on working only in video games, rather I want to concern myself with many different types of video production, so long as the project is stimulating and has potential. With regards to Casshern, it seems the director, Kazuaki Kiriya, owned a copy of Inside Out With Gadget and had long since held an interest in my work. It was by that chance that I came to participate in video production for Casshern.

The parts that I was actually in charge of included concept design, CG modelling, scenery production and effects, among many other things; I was basically a jack of all trades. I dare say it was not a normal movie, and I was a unique person on set. Up to that point I had been focused on working on videos in full CG and had not really come into contact with videos that mixed live action and CG, so for me it was a deeply interesting project.

Afterwards, the number of films combining live action footage with CG greatly increased. This is related to the fact that, over several years, the creative enviroment of film, video, and photography became fully digitized and the synthesis of live action and CG became much easier. IMABIKISOU, for instance, is not full CG and instead uses the same technique as Casshern, mixing CG with live action.

CG : Recently, you've returned to the video game medium for the creation of the Japanese-exclusive, precisely with that new title, IMABIKISOU. Which were the reasons that drove you back to the games industry and what, do you think, has changed after all these years, in the process of video game making?

SHONO : The gaming industry has developed as a business. I feel that because the scope of games has also increased in size and the production style has become very systematic, it is now difficult to produce something outside of the pre-existing genres. Developers seem not to be interested in pursuing anything outside the established user base, and the established game formats. I think, back when I was involved in making games, it was a period when they included the expressive potential of movies and video, and other types of media, instead of being limited to traditional notions of what a game should be. But now that the move from analogue to digital in video and other media is complete, the former predominance of diverse video expression in CG has been lost, and because of this, developers no longer pursue the potential of visual expressionism. Surely this is another reason for the difficulty in producing diverse games in todayís market.

The PS3 HD format has enabled visual expression at the same level as motion pictures. In fact, Imabikisouís processes of photography, editing, and post-production were roughly at the same level as that of an actual movie. Although the image quality of movies has drastically improved, thanks to large data capacities and precise production schedules, I get the feeling that it will take time to uncover any new possibilities beyond this.

CG : Personally I've always felt very strongly about your work. GADGET was one of the first mature games I had the pleasure to play and I still feel shocked when I watch the final sequence, so ambiguous and intricate; the whole game remained a puzzle for long in my mind. All those work experiences must have left some deep memories - looking back to that part of your life, what do you remember the most?

SHONO : GADGETís entertainment value, as a video game, was considerably slim, and interactivity was also greatly reduced. My approach to this project was not to aim to create a normal video game, rather my main objective was to realize a different form of visual expression through interactive control in a game world modeled in full CG.

Consequently, the workís emphasis was not on action or gameplay, but to give a strong sense of presence to the game world and its environment. With the oppressive atmosphere and the preservation of tension and mystique, I was aiming to derive a quiet catharsis, based heavily on an element of ambiguity. Perhaps current video game developers have dismissed this approach, but at the time, this method of influence was very much a possibility. For this reason, I think it leaves a very different impression to other games.

CG : In spite of those dramatic changes in the industry, do you intend to create or participate in the creation of new video game projects somewhere in the future?

SHONO : Right now, no. Itís a shame, because I have ideas, but the Japanese video game industry has become very conservative; both makers and players have settled, businesslike, into genres that have become stale and I think itís difficult for them to accept difference and innovation. At any rate, if the opportunity arose, I think I would like to bring my accumulated skills and ideas together into a tangible form.

NEW VENTURES Haruhiko Shono was born in 1960. From early on in his career, he has always been related to the latest computer graphic technologies. In spite of his absence from the world of videogame creation, with the exception of his recent project with Chunsoft, Shono has been investing largely in special effects for films such as the 2006 Japanese action blockbuster Arch Angels, as well as in the production of music videos from the Japanese dance music group Exile. His official website, Will O The Wisp (currently under construction) will include news related to his latest works, as well as concept art and CGI work.

LIST OF WORKS Alice - An Interactive Museum

Based on the paintings of Kuniyoshi Kaneko, Alice Interactive Museum was one of the earliest CD-ROM games for the PC and MAC. Inside the space of the museum, the player must visit different rooms and find a number of playing cards by solving the enigmas presented in the paintings. An inspiration for dozens of titles to come, given its proprietary style of interaction, this eccentric adaptation of Lewis Carrol's masterpiece has become a rarity among adventure game collectors. L-ZONE

Described as a 'silent adventure', L-Zone follows a pattern similar to Shono's first adventure while presenting an abrupt change of scenery: instead of a museum of fine art, the adventure takes place in a labyrinth of industrial spaces and hi-tech devices. Highly experimental, L-Zone was the launch platform for new design features such as video implementation. Gadget: Invention, Travel and Adventure

In a period of videogame expansion, Gadget was one of the first titles to combine the latest audiovisual technologies with the narrative maturity that could only be found in selected Interactive Fiction adventures. Hardly could such a complex, immersive and mind-bending experience be described. Inside Out With Gadget

Given the commercial success of Gadget, with the great sales generated both in the Macintosh and PC departments all over the world, Haruhiko Shono decided to explore further into the world he had created by making use of high quality renders printed in paper, along with carefully written texts that took the world of Gadget to another level of depth. GADGET TRIPS / MINDSCAPES

A mesmerizing experience, Mindscapes is a hour and half long video consisting of apparently inarticulate sequences of pre-rendered objects and characters from the game, often using fractal displays in between. Using some of the themes composed for the original game, this video is accompanied by an extended series of quasi symphonic movements authored by Koji Ueno. Gadget: Past as Future

Four years after the original release of Gadget, Haruhiko Shono continued with a renewed version of the 1993 digital master-piece, offering superior quality renders and longer hi-res video sequences. The game was also translated into several languages in this new edition, counting with a rare conversion to console format with a PlayStation release exclusive to Japan. Virtual Drug

Long before its release in DVD format, in 2001, Virtual Drug was possibly one of the first works made by Shono in the field of computer graphics and video - originally edited in 1990 in VHS. Together with a pair of special goggles (known commonly as Rave Spex), Virtual Drug is an essential item for all those interested in exploring the origins of the world of Gadget, namely the concept of the mind trip. Kamaitachi no Yoru 2

Given the fall of the CD-ROM era and of Synergy, Haruhiko Shono began to integrate in new game design teams as a CGI director. Such was the case of this Super Nintendo sound novel sequel, released for the PS2 and later to the PSP, under the name of Kamitachi no Yoru. Casshern

In 2004, Casshern was hailed as one of the most visually impressive film features. This high budget movie production is a remake of a cult anime movie from 1973 (Neo Human Casshern), this time made using the latest CGI technology: Shono was invited to supervise this department and help give shape to this chaotic alternate history scenario. Imabikisou

Released exclusively in Japan for the PS3 and later for the Nintendo Wii, Imabikisou is horror adventure game that comes with top quality visuals and atmosphere. The production of this exquisite environment, reminiscent of recent Japanese terror film and television, was attained by intertwining live footage with real actors with pre-rendered locations - animated and filled with details. The game was released by Chunsoft, the reference for top quality adventures in Japan, also responsible for other prominent titles such as Machi or 428. UNRELEASED WORK

During a lifetime of digital productions, Haruhiko Shono has initiated a number of projects that never reached completion of did not qualify for release. Jigoku no Kisetsu and VLF are the examples of two pilot movies that never made it into full length features. Never published elsewhere before, some images from the movie are now available to the public in the parent blog, Pixels At An Exhibition.

|